In the Pixar movie, Up, one of my favorite scenes is the one you see below. Before Carl became the grumpy old widower whose house was lifted by balloons, he was a young man whose wife, Ellie, liked to watch clouds with him and point out what they looked like.

Carl and Ellie, from Up (Pixar, 2009), image courtesy of Pixar

“To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees,” was once stated by the French writer and philosopher Paul Valery (1871-1945). When Carl and Ellie were watching clouds, they didn’t just see an amorphous mass of water vapor; they went beyond the form of these objects, drawing shapes from memory and making them fit within the constraints of the cloud’s form.

In Proust was a Neuroscientist, Jonah Lehrer wrote about how the painter Cézanne showed the difference between seeing and interpreting. During his time, critics who derided his work said that his paintings were unfinished. Indeed, when you look closely at his work, he focused on form and color without objects being outlined. For Cézanne, our impressions required interpretation―to look is to create what you see. The way he painted was the way our eyes really saw the world. Our brains added the details after.

Like Carl and Ellie, I also look at clouds in different ways. Some of you may know that this has been keeping me happily occupied:

Rorsketch

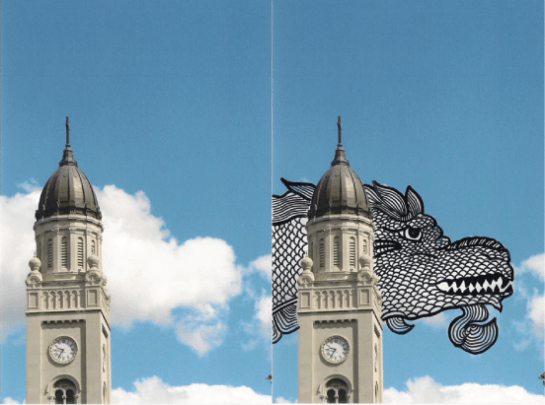

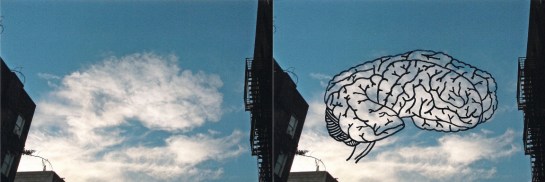

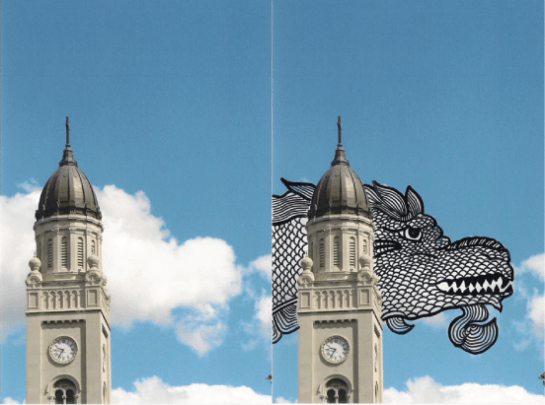

An example:

Rorsketch, Cloud #17, A dragon obliviously glides past a church.

In the middle of doing a hundred of these, I began to see the multiplicity of interpretations people can have from one simple object. I realized that their perceptions are affected by things such as age, profession, and culture. Also, too many strangers have stopped me as I took yet another photo of the sky while jumping up and down with baffling excitement. Why was I so happy? Because I’m seeing a dinosaur! Aren’t you? I wanted the project to be more accessible to people by designing a public interface.

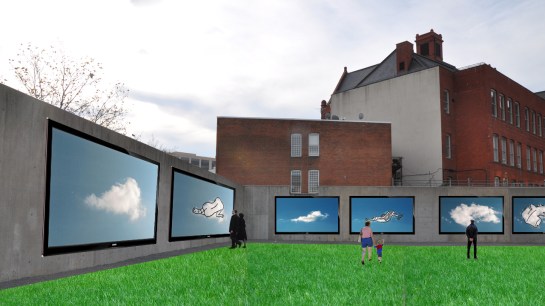

While parks would be the ideal place, I wanted something that would be secure and make the interface safe from vandalism. I decided to place it in MoMA PS1, which had an open area, a rooftop and two alcoves across the courtyard. Aside from parks, rooftops are a great way to see the sky; they lend a meditative, reflective state that is not unlike being on top of a mountain.

Although PS1 looks bare, it’s a popular place for certain events, especially their summer parties and the Young Architects Program. I wanted to transform it from this:

MoMA PS1

To this:

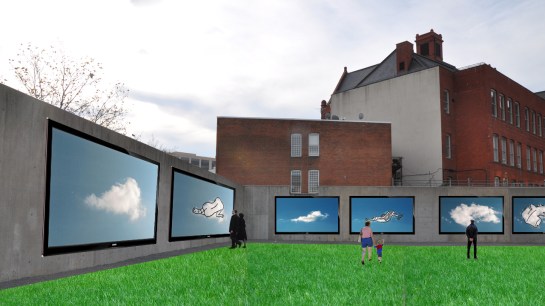

Rorsketch at MoMA PS1

An overview of the project:

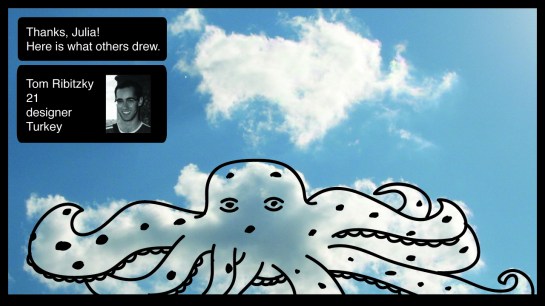

Rorsketch is a public collaborative art project that allows MoMA PS1 visitors to draw their interpretations of clouds on a digital interface on the rooftop. Using data gathered from visitors’ smartphones, the drawings will be automatically tagged with the sketcher’s name, age, profession, and country of origin. People can view the most recent interpretations in the courtyard. A gallery of these drawings with their metadata will be displayed in the two adjacent alcoves. These drawings will be documented online.

To gain admission to MoMA PS1 and to let the digital interface recognize the person creating the drawing, visitors will download an app on their smartphones:

Rorsketch, the mobile app

The mobile app will allow them to enter their information; namely, their name, age, profession, and country of origin. Alternatively, they can also sign in using their social networks:

The app will ask for some information that will be used to tag the visitors' drawings.

Next, visitors will also get a taste of what the project is about by requiring them to draw on a cloud:

The Rorsketch app requires you to draw on a cloud before you get your QR code.

When you submit your drawing, you get a unique QR code that will allow you access to PS1 as well as the digital interface.

The Rorsketch mobile app gives you a unique QR code that serves as your ticket.

When visitors are at the rooftop, they will encounter a 22-inch transparent LCD screen that will show a live video feed of clouds. On days where there are no clouds, a pre-recorded video will be shown.

Visitors will encounter the Rorsketch digital interface on the rooftop.

A visitor who wants to draw will have his QR code scanned to be identified. The visitor can pause the feed if he or she sees a cloud to be drawn.

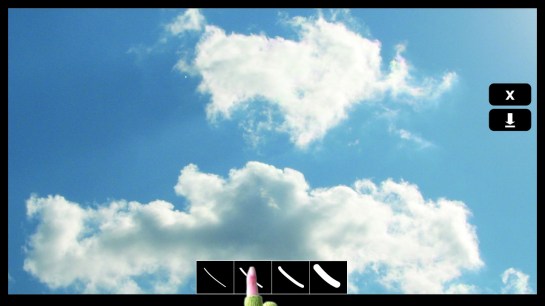

A visitor who wants to draw on a cloud can pause the video feed.

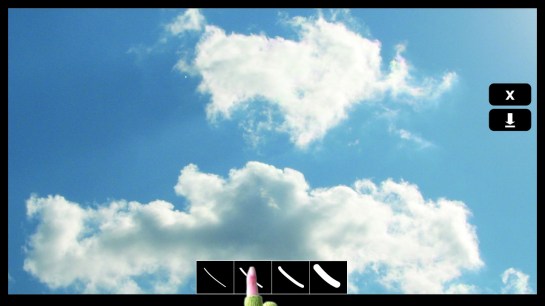

After pausing, the visitor will see that a palette of brushes appears, as well as the option to save or delete:

A visitor can choose from a palette of brushes with which to draw.

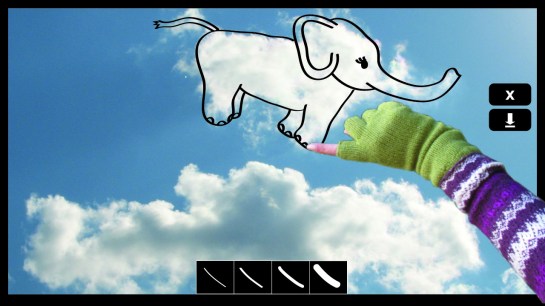

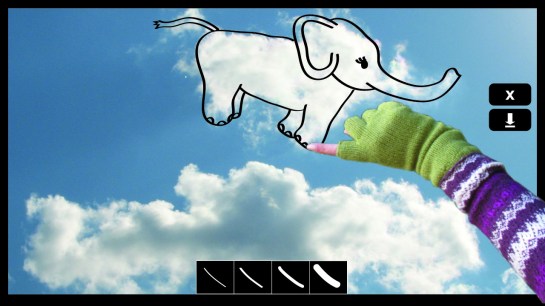

In this case, she sees an elephant:

The Rorsketch Digital Interface allows you to freeze a live video feed of clouds, and draw on it.

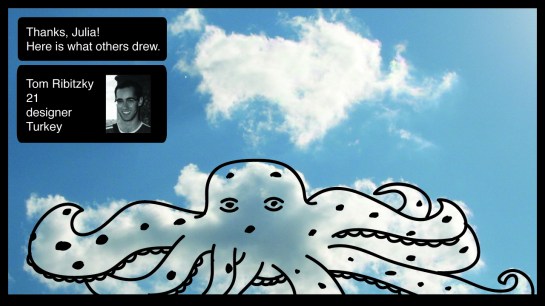

When the visitor saves the drawing, which is automatically tagged with his or her metadata, the interface may show a drawing by another person who may have interpreted it in another way:

After a visitor submitted a drawing, the interface can show another drawing on the same cloud, if it so happens that another person interpreted it in another way.

Meanwhile, down in the courtyard, visitors can view the most recent drawings through large LCD screens:

In the PS1 courtyard, visitors can view recent drawings with paired LCD screens, one showing the cloud and another showing the cloud with the drawing.

Rorsketch in the MoMA PS1 courtyard and adjacent alcoves

For the two small alcoves just across the courtyard, visitors will encounter a gallery of clouds and their drawings, together with the metadata of the people who drew them:

Rorsketch gallery in the MoMA PS1 alcoves

The Rorsketch gallery in the PS1 alcoves

In the alcoves, the clouds and their drawings will be tagged with the sketcher's information.

Reflecting on this project, I wondered about this idea of recording humanity’s perception, similar to cave paintings made thousands of years ago, such as this one from the Chauvet cave, recently the subject of Werner Herzog’s documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams:

cave paintings at Chauvet, France (Image courtesy of the New Yorker)

I am fascinated by cave paintings because they are literally fragments of why our ancestors were the way they were; a record of what they saw. According to Michael Hofreiter, an evolutionary biologist at the University of York in England, whose team conducted research on cave paintings:

“It’s an enigma, but it’s also nice to see that if we go back 25,000 years, people didn’t have much technology and life was probably hard, but nevertheless they already endeavored in producing art. It tells us a lot about ourselves as a species.” (from an article in the NYTimes)

What if we had a way to record humanity’s perception over time? What will it say about the way we see?

Visit the project’s site here.

A postcript:

This was created as a final project for my class in Design for Public Interfaces at SVA’s Interaction Design program. Thanks to my instructors, Jake Barton and Ian Curry of Local Projects, as well as our guest panel for their valuable feedback.